The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) commemorates Black History Month with wide-reaching programs that elevate the theme of “African Americans and the Arts,” using art as a platform for social justice. Black History Month also features the museum’s “NMAAHC Kids Learning Together” program, providing an opportunity for kids to virtually meet Black beekeepers, a Black scuba diver, and a Black rock climber. All “NMAAHC Kids” programs are free with advance registration. Explore the museum’s Black History Month online resources, including a dedicated Black History Month webpage at nmaahc.si.edu/Blackhistorymonth.

“The National Museum of African American History and Culture celebrates Black achievement year-round, but we look forward to taking time in February to explore art as a platform for understanding history, struggle, social justice, and triumph,” said Kevin Young, NMAAHC’s Andrew W. Mellon Director. “In doing that, we will put the spotlight on paintings, sculpture, photographs and fiber works that were made to mobilize people to create a better world by harnessing the power of protest, defiance and resilience.”

February Programming Schedule

All programs are free; advanced registration is required unless noted below.

- Education Programs:

- Feb. 2, 11 a.m.–12 p.m.: NMAAHC Kids Learning Together: Meet a Beekeeper!

- Feb. 9, 11 a.m.–12 p.m.: NMAAHC Kids Learning Together: Meet a Diver!

- Feb. 20, 11:30 a.m.–12:45 p.m.: Big Objects, Big Stories: Plywood Panel Mural from Resurrection City

- Feb. 23, 11 a.m.–12 p.m.: NMAAHC Kids Learning Together: Meet a Rock Climber!

- Specialty Tours:

- Feb. 1, 1:30 p.m. – 3:45 p.m.: Big Objects, Big Stories: The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture by Jacobs Lawrence

- Throughout the month: Spotlights: Freedom Now! The Modern Civil Rights Movement (1945-1968)

- Throughout the month: Slavery and Freedom Highlights Tour

- Throughout the month: Making A Way Out of No Way Highlight Tour

- Throughout the month: Big Objects, Big Stories: Afrofuturism and the Black Lives Matter Movement

- Public Programs:

- Feb. 9, 6:45 p.m.–9 p.m.: A Seat at the Table: Art: A Tool for Promoting Equity, Fulfillment, and Self-Care ($40)

- Feb. 15, 7 p.m.–9 p.m.: Iconic Looks: Muse: Cicely Tyson and Me: A Relationship Forged in Fashion

- Feb. 17, 1 p.m.–3 p.m.: Visual Art Workshop: Gel Plate Printing ($20)

The Sweet Home Café

The Sweet Home Café brings families and friends together year-round to celebrate African American history and culture through food and hospitality. During Black History Month “Chef’s Table” events, every Friday from 12 p.m. – 3 p.m., guests can enjoy special menus created by guest chefs from across the country. Participating chefs will tell stories from their heritage through curated menus from the Sweet Home Café kitchen. For more details, please visit the Sweet Home Café’s webpage. Entry to the museum includes access to the Sweet Home Café. Special Dine and Shop passes are also available for access to the Sweet Home Café and gift shop only.

- Sweet Home Café Black History Month Chef’s Table Series:

- Feb. 2, 12 p.m.–3 p.m.: Sweet Home Café Chef’s Table with Chef Chris Scott

- Feb. 9, 12 p.m.–3 p.m.: Sweet Home Café Chef’s Table with Executive Chef Ramin Coles

- Feb. 16, 12 p.m.–3 p.m.: Sweet Home Café Chef’s Table with Executive Chef Jeff Cortez

- Feb. 23, 12 p.m.–3 p.m.: Sweet Home Café Chef’s Table with Executive Chef Tarik Frazier

Items on View During Black History Month

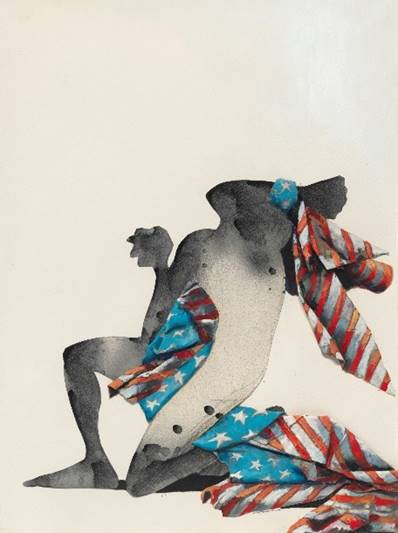

Benny Andrews is best known as an artist, educator, and activist. Militant is an excellent example of Andrews’s interest in placing themes of social justice into his art. His image of a man on bended knee recalls the figure of an enslaved man, bound in chains, designed by Josiah Wedgwood during the 1780s for the Society for the Abolition of Slavery. Titled “Am I not a man and a brother?” the image became a rallying cry for the abolitionist movement.

In Andrews’s contemporary version of Wedgwood’s image, the figure is swathed in two American flags. By doing so, he evokes themes of African American patriotism while challenging the notion that Black Americans are unworthy of enjoying the full benefits of being United States citizens. This object is currently on view in the museum’s “Reckoning: Protest. Defiance. Resistance.” exhibition.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Ethiopia, ca. 1921

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Ethiopia is widely considered the first Pan-Africanist artwork created in the United States. It provides a visual embodiment of the New Negro Movement—an era during the 1920s characterized by an increased recognition of artistic and cultural production by Black people, and a consciousness of racial heritage and pride.

- E. B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson commissioned Fuller to createEthiopiafor the Negro Exhibit in the America’s Making Exposition. An image of the sculpture graced the cover of the exhibit’s publication describing it as, “A Symbolic Statue of the EMANCIPATION of the NEGRO RACE.” Fuller’s work links the cultural achievements of ancient Egypt as well as the Ethiopian resistance to colonial rule to a narrative of African American struggle and achievement, using the past to guide and critique the present. This object is currently on view in the museum’s “Reckoning: Protest. Defiance.Resistance.” exhibition.

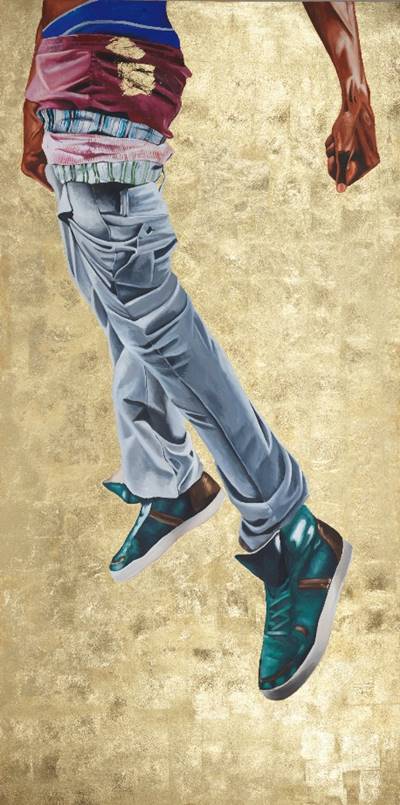

Fahamu Pecou, But I’m Still Fly, 2014

“Grave representations of Black men act like a force of gravity, restricting their mobility. We meet Black youth with fear and loathing, limiting their potential with tragic stats and stories of death. But I’m Still Fly offers an alternative narrative, one that locates the tension between aspiration and limitation. … This piece asks: What if we believed in the abilities of our Black boys more than we lamented their identity? What if we taught them that they could transcend their so-called limitations? What if we encouraged them to fly?” – Fahamu Pecou

Pecou’s painting features the fashion trend “saggin,” where underwear is worn above sagging pants. The style was popular among younger African American males and often perceived by others as a negative marker of social status. This object is currently on view in the museum’s “Reckoning: Protest. Defiance.Resistance.” exhibition.

Lava Thomas, Euretta F. Adair, 2018

Euretta F. Adair was one of more than 80 African American activists who were arrested for planning and participating in the Montgomery Bus Boycott between 1955 and 1956. Adair served on the executive board of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), founded in 1955 by Black ministers and community leaders four days after the arrest of Rosa Parks for refusing to vacate her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery city bus. The organization’s mission was to oversee the boycott, improve race relations, and uplift the general tenor of the community.

Lava Thomas’s drawing of Adair is one of 12 portraits in her series, Mugshot Portraits: Women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Drawn from actual mugshots of female activists, these portraits highlight the commitment and bravery of the unsung women of the movement, whose sacrifices ensured today’s freedoms. This object is currently on view in the museum’s “Reckoning: Protest. Defiance. Resistance.” exhibition.

Credit: Collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Cheryl and Charles Ward, copyright Lava Thomas.