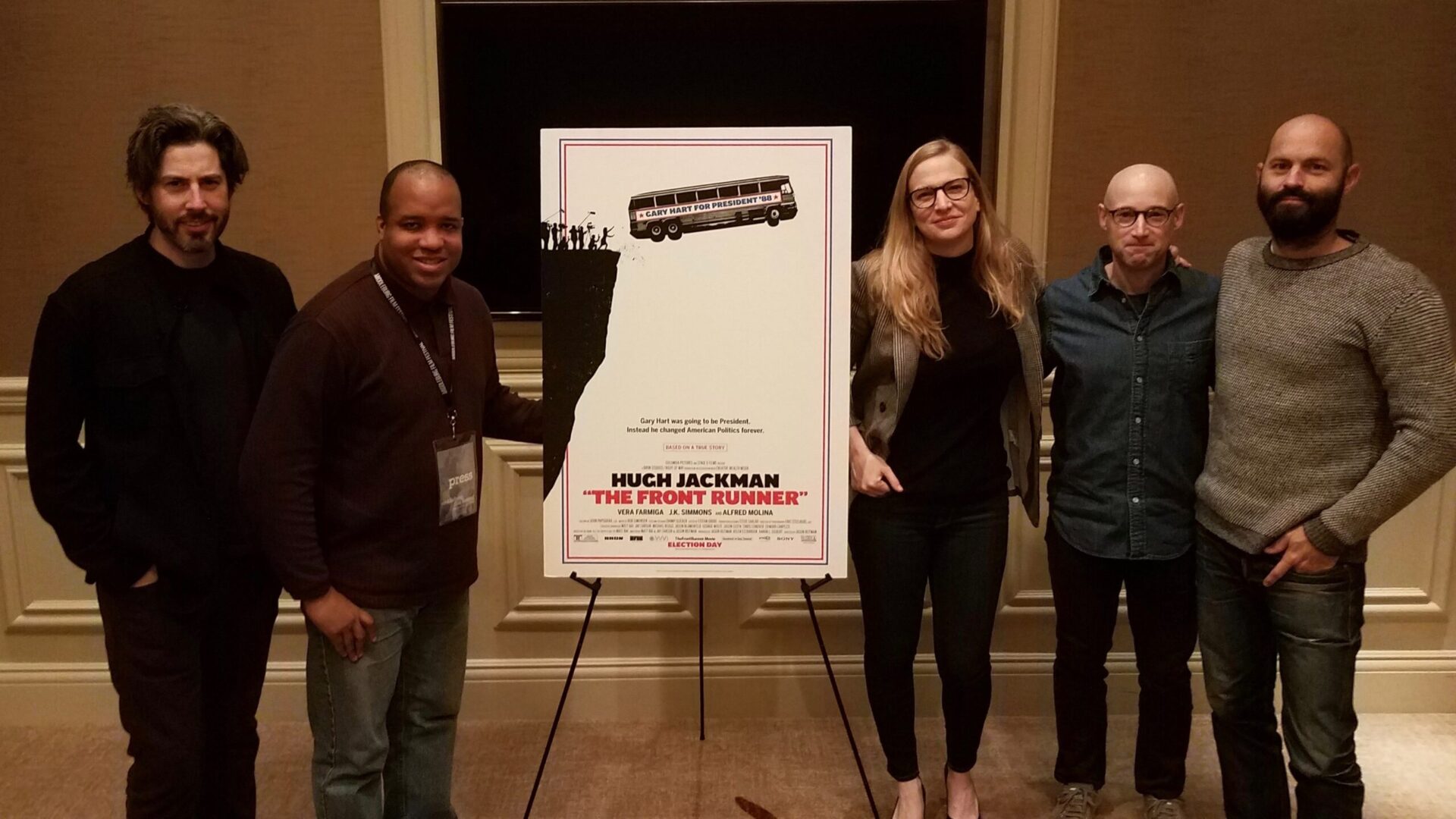

On this edition of INTERVUE, we journey back to the 1980’s to look at the journey of Gary Hart who was The Front Runner for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination until he dropped out over allegations of an extramarital affair. For those who attended the Middleburg Film Fest recently, they got their first glimpse of this film that’s due out this weekend. I sat down with director Jason Reitman, Producers Helen Estabrook & Matt Bai and screenwriter Matt Bai to talk about The Front Runner.

First, we’re going to start with you, Jason. The opening sequence in the film is such an assault on our ears, because everyone is talking like we are right now in a way. You can’t distinguish one conversation from another, until it narrows down to the people around the table, and I want to talk about that scene particularly. Tell me how you set it up and how it was done.

Jason Reitman (Director):Well, from the moment we started discussing the story as screenwriters, we were talking about the idea of relevancy.

What is important versus what is entertaining? This is the philosophical question the Gary Hart story asks us. The question we continue to ask ourselves today in the midst of this presidency and everything that’s happening. “What is important? What is the real information?” So, we began very early talking about overlapping conversations and how can we create this messy sense of real life both in the audio, but also visually and I think it was through an opening shot that was two and a half minutes and sprawling where we’re introduced to character after character, and you as an audience have to start figuring out for your yourselves who is important to this narrative? What am I supposed to listen to?

The innocuous information is braided with the important information and it’s impossible to follow all of it. It’s designed that way, and you kind of just hopefully start falling into the scenes, into these locations where you find yourself as just a participant in the room, trying to kind of keep up with all the conversations around you.

Absolutely. Matt, in regards to the book and the film, tell us about the standards employed by journalists—not like me, other journalists—covering the private lives of politicians?

Matt Bai (Screenwriter/Author of All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid): Well, I’ve covered five presidential campaigns myself. Those kinds of standards are always changing case by case, but in 1987, I think you had this flashpoint where they change very quickly, and they change because a lot was going on in the culture.

You’re ten years after Watergate, which really created change in the a way journalists viewed their role in that process, and you had the rise of feminism, you had the rise of silent majority, you had the birth of the satellite television dish and the portable dish, so I think all of that was sort of churning in the late 1980’s and what it meant was in that moment, we began to effectively treat politicians and candidates for offices more like we had treated celebrities.

And that to me has been the central struggle, really ever since and the trajectory of our politics have been towards more of an entertainment and more of a celebrity ban, and I think that’s why the movie, even though it depicts events that are so long past feel so relevant for the moment we’re in.

Helen, I want you to talk to us about the female character development in the film. In particularly, we have Lee Hart played by Vera (Farmiga) who is making sure Donna Rice is ok, even though she has a job to do, but at the same time she feels compassion for this woman, especially since it’s the first time in politics anyone has to go through that in a long time.

Helen Estabrook (Producer): I think it’s important to show all elements of this and everyone who is sort of a reverberation of the effects of the decisions that people were making, and things that no one was expecting, and I think that one of the things that’s really important for me in this film is showing a lot of what happens not just the women directly involved in the scandal, but the women indirectly involved in various scandals and women who just in general end up having to take on a lot of emotional labor often, because that’s sort of seen as the role of what they can do.

Jay, I wanted to know the parallels the audiences draw between the politics now and the politics just thirty years ago.

Jay Carson (Producer): We captured a moment in this moment, I hope we believe, we captured a moment in this movie where politics changes were everything that existed for change and there’s a through-the-line this moment in 1987 to the way politics happens today. And there’s a role that everyone plays in that. The candidates have changed; the types of candidates have changed; the journalists have changed; the voters have changed; the operatives have changed. And there’s this spark that’s lit in ’87 that we’ve seen that fuse burning for thirty years now and it seems to have exploded in American politics in the last couple of years.

This next question open to anyone. Setting aside the scandal that ended Gary Hart’s career, in the terms of political beliefs, who do you think in politics state is closer to Hart and his forward thinking platform?

MB: I would tell you I’m not punching on your question, but I’ve spent many, many years pondering that question periodically, and I think that the real answer is we do not have a political process on any side of the spectrum that has really addressed the problems of the future as boldly as I think Hart talked about it then, as politicians use to talk about it with some regularity, and I think part of that is the change in the process.

Which rewards short term thinking, which is so focused on making candidates account for these notions of character over ideas often. And as Jason often says, rewards are kind of shamelessness and so I think that you get the government that your process creates, and part of the question the film is asking us—for all of us, journalists like myself, former operatives like Jay, or voters and candidates is what role of our decisions play in creating this process and is it the best one, and is it working?

And I think that’s what people, hopefully—when it gets better experience in the early screenings, they leave the theater talking, thinking and debating, because these are big questions that people are asking themselves and this is a way to having that conversation.

Jason, I’d like to know why did you choose this project, especially considering you and I were roughly about the same age when the Gary Hart scandal went down almost thirty years ago?

(chuckles) It’s funny. As a filmmaker, one of the questions you get asked the most is “why this project?” and it’s funny, as though you were walking up to a married couple and asking them, “so, uh, why her? Why him?”

Dean, Jay, Helen, Jason, Matt: (laughter)

JR: And to a certain extent, you can’t control these things, you know? There’s these stories people want and they tell and all I know is when I read Matt Bai’s book on the Hart scandal, I was just completely taken by it and look, I’m like anyone else alive today, I’m looking for answers. We all are. It doesn’t matter what side of the line you’re on right now. Ah, hard to feel that the system is broken and that’s something that Matt did in that book, there’s something that Matt saw in that story that no one else picked up on. It’s relevant to today, and not that it has an answer for us, but it seems to be asking the right questions, and that’s why we make movies. We make movies because we have questions. I say don’t trust a filmmaker who has answers.

(laughs)

JR: I am interested in filmmakers who come to their work with questions and when it comes to politics today, I think that’s all we have are questions.

Now, there was a recent story that Hart was set up by the Bush campaign. Do you feel that the recent news will change the perception of the film, yes or no?

JR: Great question. What I love about it is that it really points to this idea of how we remember things and how we look to the past and what matters and for some people this will matter, that Lee Atwater somehow, perhaps semi-orchestrated this event. But what matters to me is this is a story about a small collection of private people who became involved in a public moment; a public moment that we all were interested in and we all felt a certain kind of “right to know” about it. And the question is, what comes with that knowledge? Do we deserve to know it? Do were want to know it? And it’s impossible to say in 2018 what is right and what is wrong in 2018. You need perspective. And what’s great about this story from thirty years ago is that we have just enough time under us to look back and really start thinking about what is our relationship with the way that we digest stories? And what do we really want to know about our potential candidates, and what flaws are we willing to put up with?

The Front Runner is in theatres THIS FRIDAY!